History on the march in Market Square

Do you hear that bell?

Hidden behind the clock on the North Church steeple, for over a century and a half, it has kept time — and marked the passage of history — in the heart of Market Square. …

In a city settled nearly four centuries ago, a mere 40 years can flash by in what seems like an instant.

Hidden behind the clock on the North Church steeple, for over a century and a half, it has kept time — and marked the passage of history — in the heart of Market Square.

Next Saturday morning, it will chime nine times, ringing in the official start of the 40th annual Market Square Day.

The inaugural celebration marked a major milestone in Portsmouth’s nearly 400-year history — the dramatic transformation of an economically depressed downtown, bisected by a five-lane asphalt wasteland, into the vibrant, brick-lined public plaza that today is the centerpiece of a thriving community of cuisine, culture and commerce.

That first Market Square Day marked more than just a physical makeover of a sleepy public square where the rich history of many buildings was hidden behind “modern” siding and signage. Part farmers market, part local music fest and performing arts showcase, part balloon-festooned picnic — it was a home-grown block party to revel in a renewed civic spirit animated both by Portsmouth’s proud past and a shared optimism about the future.

Today, Portsmouth regularly appears on national lists as a destination city — with its energized arts organizations, its status as a restaurant mecca and its ever-present opportunities to connect to our past. It also faces ongoing challenges that include parking and development pressures, and a higher cost of living that prices out artists and those of modest means.

Looking back, the late-1970s revitalization of Market Square played a crucial role in setting Portsmouth on a course to become the city it is today.

On your Market … set … go

Next Saturday, when the church bell chimes 9, a starter’s pistol will send a river of runners flowing along Congress Street, rushing through the historic downtown where Revolutionary War-era patriots once tread.

Barbara Massar, executive director of Pro Portsmouth, the nonprofit that sponsors Market Square Day, spoke of “the exhilaration I feel every year when I see those runners going up Congress Street.”

Part of what is special about the annual Market Square Day 10K is “how the race impacts the neighborhoods throughout the city,” she said. “People have gatherings and breakfast parties. It’s truly one of the unique races because of the way that the neighborhoods come out and cheer.”

Starting in front of North Church, more than 2,000 runners will dash, jog and meander down the city’s main thoroughfare …

Past Chestnut Street, site of The Music Hall (c. 1878), once labeled by Yankee Magazine “the crown jewel of Portsmouth’s cultural scene” …

Turning left past the Discover Portsmouth Center, part of which occupies the old Portsmouth Academy prep school (c. 1809) …

Then left again onto State Street past the John Paul Jones House, Rockingham Hotel and the African Burying Ground …

On through the downtown where in the very early 1800s three major fires wiped out entire city blocks …

On toward the river with Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (est. 1800) looming just across the way …

Looping past Memorial Bridge, where former Mayor Eileen Foley cut the ribbon on both the original 1923 span at age 5 and its battleship gray replacement in 2013 ..

Up the hill onto Bow Street past Seacoast Repertory Theatre, former home of the fondly remembered Theatre by the Sea …

Past St. John’s Church (c. 1807) on the site where President George Washington attended a “divine service” in November 1789 …

Down the hill past Ceres Street and its famous tugboats, once a gritty waterfront district where Theatre by the Sea found its original home in an abandoned grain warehouse and where chef James Haller ran the legendary Blue Strawbery …

On down Hanover Street and right onto Maplewood, past the ghosts of the North End neighborhood — leveled decades ago in the name of urban renewal and now the site of several new city blocks with more on the drawing board …

Past the North Cemetery, resting place of William Whipple, whose signature graces the Declaration of Independence …

Uphill past Northwest Street, site of New Hampshire’s oldest surviving wood-frame home, the Jackson House (c. 1664) …

Over the bridge spanning the Route 1 Bypass and offering a glimpse of Albacore Museum and its landlocked submarine, launched at the shipyard in 1953 …

And on and on through neighborhoods, where residents and friends stand and cheer for the runners, offering hydration and exhortations of encouragement …

Onward to Bartlett and Islington streets, into the heart of the now-flourishing West End, where two of legendary beer baron/politician Frank Jones’ Brew Yard buildings will soon house new homes and businesses …

Down Essex, Middle and Miller, then left past the South Street Cemetery, site of the tall tomb of Frank Jones (1832-1902) and the graves of 1873 Smuttynose murder victims Karen and Anethe Christensen …

Then back toward the river, left on Marcy Street to Prescott Park, the city’s grand, green front yard and gardens — center stage each summer for salt-aired arts and culture …

And Strawbery Banke, settled around 1630 and centuries later reborn as Portsmouth’s living history museum …

That’s where the race ends, but our story is just beginning …

Let’s slow down, catch our breath and explore today’s Portsmouth, settled in 1623, and how it has evolved over these past 40 years.

Flashback, pre-1978

What was Portsmouth like in the years leading up to the revitalization project that culminated in the first Market Square Day in 1978?

“The place was full of potential, but still kind of a wreck,” said local historian J. Dennis Robinson, who arrived here in 1973 after graduating from the University of New Hampshire.

Strawbery Banke, the sprawling outdoor museum set in motion by librarian-preservationist Dorothy Vaughan during a now-famous 1957 speech to the Rotary Club, had not yet matured into its current status as the centerpiece of Portsmouth’s now prospering “heritage economy.” Other nonprofit museum-landmarks — the John Paul Jones House (1758), Moffat-Ladd House (1763), Warner House (1716) and others — had been welcoming visitors for decades.

However, this was also an era when many historic buildings were being leveled in the name of progress — most notably through the ill-fated North End urban renewal, in which federal dollars were used to raze homes and uproot an entire neighborhood.

“Progress struck ‘Little Italy’ like an H-bomb. Nearly 200 homes, 400 buildings in all, were bulldozed out of sight — but not out of mind,” Robinson wrote regarding the human impact of urban renewal, which scarred the community but also inspired a new generation of activism around historic preservation.

Robert Chase of York, Maine, then working as a consultant for the N.H. Council on the Arts, formed Portsmouth Preservation Inc. in 1969 in an effort to save some of the historic North End homes. A dozen or so survived and were relocated to what is now called “The Hill.” An artist’s rendering from the time depicts a gleaming, modern commercial complex that never came to be.

Many locals will remember the former Parade Mall, anchored by an A&P grocery store, that stood on the site until it eventually went out of business. The Sheraton hotel, overlooking the waterfront salt piles, arrived a decade or so later. But much of the urban renewal land lay vacant for decades.

“Portsmouth was willing to destroy itself to find a new economy,” said Richard Candee, a longtime local preservationist and Boston University professor emeritus who for nearly 30 years ran the school’s Preservation Studies Program. He was working at Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts when he came to Portsmouth around 1966-67.

“I adopted the city,” he said, eager to pursue his passion for preservation in a place that was “small enough to get your hands around.”

Today, you may see him leading historical downtown and neighborhood walking tours for the Discover Portsmouth Center, including one titled “North End: Lost Neighborhood.”

Also the author of “Building Portsmouth (the Neighborhoods and Architecture of New Hampshire’s Oldest City),” he has been intimately involved in countless local preservation efforts, including working to obtain federal funds for a 1976 project to preserve and connect two 1810-era buildings at the former Portsmouth Public Library, now home to Discover Portsmouth.

In the mid-1970s, he recalled, despite considerable positive momentum around preservation, the downtown business district was languishing — “It was just dead.” In his view, there had been minimal investment in Market Square and its side streets essentially since the Great Depression.

Instead, cosmetic efforts to modernize downtown storefronts not only failed to draw shoppers, they had the effect of masking the signature element that could, and eventually would, stimulate commerce — the tired but history-rich cityscape.

In fact, much of Portsmouth’s historic core owes its survival to the fact that, across many generations, owners simply did not have the money to tear down old buildings and redevelop their properties — a phenomenon known as preservation through poverty.

However, “the idea that historic preservation could have an economic impact” had not yet taken hold among the city’s old guard, said Candee. There was even a plan backed by the Chamber of Commerce to remove additional downtown buildings and replace them with more surface parking and mall-like retail space.

“Guess what,” he observed, “the problem isn’t the buildings. They were the draw.”

Still, local banks that owned aging downtown structures were more inclined to demolish than renovate and preserve.

Local attorney Peter Loughlin, a Portsmouth native who was named city attorney by then City Manager Calvin Canney in 1971, was at the center of early legal initiatives that led to the creation of the city’s Historic District. In a fairly short span, banks moved to tear down several significant buildings. For example, Paul’s Market on Daniel Street was flattened to make room for a short-lived Indian Head Bank drive-through.

For Loughlin and others, the trend became “a catalyst to say ‘Hey, we’ve got to do something.’”

From demolition to revitalization

Pre-1978 Portsmouth faced considerable economic pressure. Pease Air Force Base and the Navy Yard were the longtime twin engines of the local economy. But the shiny new Newington Mall — anchored by retail chains Montgomery Ward and J.M. Fields — was pulling in area shoppers and stoking fresh fears about the fate of the depressed downtown business district.

Loughlin — asked during a recent interview in his law office in the 1747 Leonard Cotton House what triggered the move to revitalize Market Square — responded, “Two words: Bob Thoresen.”

Of course, the effort required countless hours of work by local officials, business people and volunteers, but “it was his idea,” Loughlin said of the former city planner. “It took Bob’s vision and salesmanship” to begin the transformation from a quaint but economically listless downtown to a pedestrian- and business-friendly public square — “a place you want to be.”

Thoresen arrived in Portsmouth in December 1971 with a master’s in regional planning from Syracuse University following a stint in the Army and a year as director of community affairs in Manchester.

“They referred to us as the Kiddie Corps,” Loughlin said of a new generation of city officials that also included Economic Development Director Ray Richardson, Library Director Sherm Pridham and others.

President Gerald Ford had enacted the Community Development Block Grant program in 1974 and Portsmouth pulled in $796,000 per year for three years starting in fiscal 1975-76. In that year’s annual report, City Manager Canney wrote, “Portsmouth’s future belongs to those who actively participate in the many decisions that must be made, and I would encourage you to become actively involved in the affairs of your city.”

The spirit of civic activism and optimism for Portsmouth’s future was shared by local residents and business people, as well as newcomers — and several smaller downtown beautification projects paved the way for a grand Market Square revitalization scheme.

“We saw this as part of our economic development strategy,” Thoresen said. “But it was a hard sell to convince the City Council.”

The plan to widen downtown sidewalks and reduce the number of storefront parking spots was of particular concern to longtime business owners concerned about the impact change might have on their economic livelihood.

“Not everything was rosy,” Thoresen recalled. “Businesses were terrified that we’d make things worse than they already were.”

Meanwhile, efforts to impose new rules that would halt the demolition of historic downtown buildings “created an absolute furor with all the banks,” he said. The eventual enactment of a Historic District Commission law crafted by Loughlin and Thoresen “basically stopped demolition.” However, in several cases permits had already been issued. So when a key building was leveled to make room for a bank drive-through, “it created a huge controversy” that stoked even stronger support for preservation.

The point was not that “every old house should be turned into a museum,” said Candee, but to “keep buildings standing” that were integral to the historic cityscape.

Complementing the local preservation movement of the 1970s, Thoresen said, “We created a visual environment program” to help showcase the city’s built-in historic appeal. This included providing historical research and “free technical assistance to store owners or business owners who were willing to invest in their storefronts.”

Thoresen also channeled Community Development Block Grant funds to reshape the footprint as well as the look and feel of Market Square, which at the time was a wide expanse of asphalt. “It was very uninviting,” he said. “It was very difficult to cross the street.”

The wide brick pedestrian plazas, trees and benches locals and visitors enjoy today were added to create a more welcoming downtown space that Thoresen and others thought of as the city’s “living room.”

Welcome to Market Square Day, est. 1978

Among those inspired by Portsmouth’s potential and passionate about celebrating it was Monika Aring, who obtained grant funding from the New Hampshire Council for the Humanities and spearheaded a group of citizens to organize the inaugural Market Square Day.

Her daughter, Antje Aring Bourdages, is now president of Pro Portsmouth’s board of directors. “The spirit of Market Square Day was to showcase local craftspeople, local performers and local businesses,” she said. “I think we’ve really tried to keep it very true to the original mission.”

In 1978, the family had recently moved to town from Park Slope in Brooklyn and became immersed in civic affairs. Her father, architect and artist Roomet Aring, designed logos and balloon arches for the event; he also worked at rehabilitating historic buildings and was “deeply passionate about revitalization and restoring what already exists.”

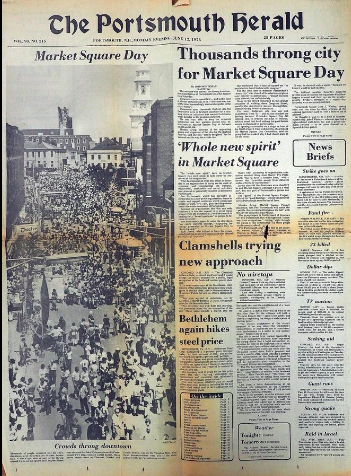

Bourdages, then 9, recalls helping blow up the balloons and said of the first Market Square Day, “I remember it being a really big deal.” The front page of the Portsmouth Herald that Monday exclaimed: ‘Whole new spirit’ in Market Square.

“It seemed like everybody you knew was downtown,” recalled Loughlin, who ran in the first 20 or so Market Square Day races.

“The most incredible experience,” wrote the late historian Bruce Ingmire, was seeing the works and performances of local creative artists. “Each of us was struck with the incredible talent that filled this ‘old town by the sea.’ We had a new impression of Portsmouth. We knew many performing artists, but seeing them together thrilled us. The old shipbuilding capital had become a unique 20th-century community.”

Robinson, who remembers performing the song “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic” with the Austin Street Singers that day, said, “The musicians lived in town; the mimes and the writers lived downtown; the artists lived downtown.” He noted Portsmouth even had two mime companies, Kitchensink Theatre and Pontine Theatre.

“A lot has changed since then, but in other ways things haven’t changed,” said Pro Portsmouth’s Massar. The festival still plays out upon that same brick-lined square and it still focuses on the same “four pillars — arts, culture, history and community.” The city’s signature celebration, she said, “has its foundation in those very bricks.”

In the words of historian Ingmire, “It was local people celebrating the revival of the city’s downtown — a revival that marked the marriage of the arts and history that continues to this day.”

Arts at heart

A Theatre by the Sea production of “Oklahoma” kicked off the fifth summer season for the Prescott Park Arts Festival in 1978. Also staged at the riverfront venue during those early years — “Carousel” (1975), “The Music Man” (1976), “Guys and Dolls” (1977) and “Fiddler on the Roof” (1979).

Though noise complaints from nearby neighbors have drawn negative attention in recent years, the festival is still going strong. PPAF estimates it has reached more than 3.5 million people through more than 10,000 productions and presentations since 1974.

Theatre by the Sea, established in cramped quarters on Ceres Street in 1965, eventually moved to Bow Street around 1978 with help from philanthropists Joe Sawtelle and Sumner Winebaum, in the space now home to the Seacoast Repertory Theatre.

The Rep, preparing for its summer production of Monty Python’s King Arthur spoof “Spamalot,” describes its mission as being “committed to the cultural richness of the Seacoast region through the shared experience of live theater and its youth, teen and senior educational programs.”

Opened 100 years earlier as a performing arts hall, The Music Hall was a worn-out E.M. Loew’s movie house called The Civic back in 1978. Saved from demolition and renovated in spectacular fashion in 1987, it earned recognition as an “American Treasure” from the U.S. Senate in 2003 and today hosts an incredible range of music, theater, cinema, comedy, readings from notable writers and talks by local thought leaders.

With many other arts and cultural organizations including 3S Artspace, Pro Portsmouth, the N.H. Art Association, Portsmouth Music and Arts Center, the Player’s Ring and many more, a survey conducted by Art-Speak, the city’s Cultural Commission, estimated the local arts sector generated an economic impact of $41.4 million in 2011.

Also, by drawing attention to areas of concern that include inadequate funding for organizations and performers as well as the lack of affordable creative workspace and housing, the survey also offers a reminder of the ongoing need for audiences and patrons to offer generous support.

“Groups like ours and events like this don’t take place without the community believing in them,” Massar said. “These things don’t just happen because you want them to happen — you have to literally put your money where your mouth is.”

Evolution of a ‘Restaurant Mecca’

The reputation of Portsmouth and its Seacoast environs as a destination for creative cuisine also has its roots in the 1970s — more specifically, on Nov. 18, 1970, when chef James Haller opened the fabled Blue Strawbery on Ceres Street.

Now a best-selling author regarded as a pioneer of New American cuisine, he had been open only a short time when on a stormy night in January he served a table of traveling patrons who turned out to be journalists from Boston. Recounting the tale during a talk for the CreativeMornings Portsmouth lecture series, Haller said, “About three weeks later, Boston Magazine came out with a big headline on the cover, ‘For a Great Dinner in Boston Drive to Portsmouth, NH, and the Blue Strawbery’.”

By infusing an old building with fresh energy and “developing something that drew people,” Candee said the colorful entrepreneur was among those who helped give passing motorists of the mid-1970s a reason not to “zoom by the exit” at Portsmouth.

Decades of memorable local chefs and restaurants followed. And today many credit Haller with playing a key role both in downtown Portsmouth’s eventual revitalization and in the area’s emergence as a culinary mecca.

Not too long ago, the Boston Globe ran a headline: “Chefs cooking up a food revolution in Portsmouth, N.H.” The article spotlighted local James Beard Award honorees Matt Louis of Moxy, Evan Hennessey of Stages at One Washington in Dover and Evan Mallett of the Black Trumpet Bistro at 29 Ceres St. — the former home of the Blue Strawbery.

Planes, subs and heavy equipment

The city’s economy in the late 1970s was buoyed, as it had been for many years, by Portsmouth Naval Shipyard and Pease Air Force Base.

The shipyard, established not long after the American Revolution when John Adams was president in 1800, launched its first vessel, the 74-gun warship USS Washington, in 1814. Workers began building submarines during World War I and more than 75 subs were constructed there during World War II.

Now focused on upkeep of the Navy’s nuclear-powered undersea vessels, it remains a major local employer — having successfully fought off periodic congressional attempts to close it. Its motto remains “Proud of our past … Ready for the future” and onlookers still line the riverbanks every time the tugboats escort a submarine into town for repairs.

However, the looming threat of base closure came true at Pease in late 1988, sending shockwaves through the area since the Air Force personnel stationed there had become part of the fabric of the community as well as the local economy. The base was closed for good on March 31, 1991, but is still home to the N.H. Air National Guard’s 157th Air Refueling Wing.

The relatively quiet early years brought fears that it might become a traffic-snarling commercial airport, or worse, sit vacant. But today it has evolved into the bustling Pease International Tradeport, with more than 250 companies employing some 9,500 people — and with limited passenger flights, mostly to Florida, offered by Allegiant Air at Portsmouth International Airport.

“It ended being much more successful for the city than the Air Force base was,” Thoresen said.

In terms of its ongoing appeal to business tenants, “One thing that makes Pease different is that you’re a 15-minute bicycle ride from the 17th century and the 18th century,” added Loughlin, who has served on the Pease Development Authority since 1990.

In some respects, the closure of Pease ended up taking some of the development pressure off the downtown area, Candee said.

However, the real estate development that failed to materialize in the aftermath of the long-ago urban renewal project has finally taken hold, some would say with a vengeance. In fact, driving south from Maine across the Piscataqua River Bridge (opened Nov. 1, 1972) one can not only see the North Church steeple but also big brick buildings where the North End neighborhood used to be.

“We now call it new Portsmouth. It’s a separate community,” Robinson said of the towering new city blocks between Hanover and Deer streets, part of an ongoing downtown development boom that has spawned not only complaints but also legal action.

The empty parking lot next to the Sheraton hotel, slated to become a development called North End Portsmouth, is now set to move forward after two years of board and legal appeals of its approval. Several other significant developments are in the works nearby.

Though they share mixed feelings about the structures themselves, Thoresen, Candee and Robinson tend to see the current building boom as part of the natural evolution of a city that, while it may be experiencing growing pains, is on the whole as healthy as it has ever been.

“Are they the best buildings that could be created there? Probably not,” said Thoresen, but “if you compare that to what was there before” — a closed-down mall and its parking lot — “it’s a quantum leap.”

Candee, the architectural historian, refers to the new construction there as “purely contemporary urban infill buildings … just neutral blah buildings” — with one common theme, they’re all about one story too high.

Robinson sounded a realistic note about the economic factors that affect today’s developments. “You can’t build the Rockingham Hotel at today’s dollar, so we end up with buildings that are architecturally less than the buildings that we prize in town.”

However, “we’re still attracting people from all over the world to a walkable heritage town.” With its unique mix of history and a flourishing artistic community, he said, “this is a cultural center embedded in an authentic historic town.”

And though gentrification is certainly an issue, he suggests the people with the deepest pockets are also those best equipped to devote dollars to the historic and cultural institutions that so desperately need them — citing Sumner Winebaum and the late Joe Sawtelle’s philanthropy on behalf of Theatre by the Sea, Seacoast Rep and many other causes, and The Press Room founder Jay Smith’s generosity in helping to save The Music Hall.

“We all think back with nostalgia.” But Robinson said that, for someone who’s always “got one foot in the 20th century,” he is also “very focused on where we’re headed.”

Time marches on

Today, some may say Portsmouth has strayed from what it once was — grown too upscale and touristy, too tall and blocky in the newer cityscape, more gentrified and definitely more expensive.

While others — Loughlin and Thoresen, Candee and Robinson among them — maintain Portsmouth is right on course. That history at its essence is a continuum of change and, though some of these changes may not match our vision, on the whole this little city by the river does a pretty solid job at cherishing and preserving what we are so fortunate to share.

“Each generation actually has a different Portsmouth,” observed Candee.

And in a city settled nearly four centuries ago, a mere 40 years can flash by in what seems like an instant.

But that bell, up in that tower, has counted every single hour. It rings out 156 times each day. All tolled, that’s more than 1.1 million chimes since that first Market Square Day in 1978.

Loughlin — noting the North Church bell was cast two years before President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in 1865 — observed, “That same bell would have been striking when people were down there mourning him.”

The next time you hear it, may it connect you to the spirit of history and community that resonates between the tall brick walls of Market Square.

John Breneman, a former Portsmouth Herald writer and editor, works as a copywriter at Vital Design.